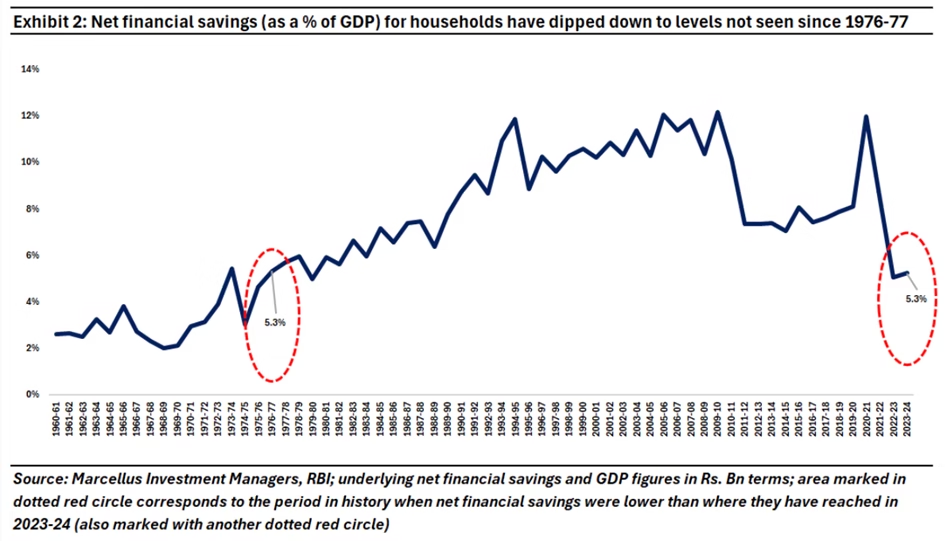

Two striking trends are unfolding in India’s household balance sheets. On one hand, net financial savings have plummeted to levels last seen in the late 1970s. On the other, the structure of household borrowing shows that India’s mortgage penetration remains among the lowest globally, even as non-mortgage borrowing is disproportionately high. Together, these charts reveal the unique financial dynamics shaping India’s economy today.

Net Financial Savings at Multi-Decade Lows

The household net financial savings as a share of GDP have collapsed to just 5.3% in FY24, a level not seen since 1976-77. For decades, household savings were the backbone of India’s financial system, peaking at double-digit levels of GDP during the 2000s. These savings provided the capital that funded both government borrowing and private investment.

The current decline raises important concerns. Households are either consuming more relative to income, diverting funds into physical assets like gold and real estate, or taking on debt at a faster pace. High inflation and weak real wage growth over the past few years may also be squeezing the ability of families to save. The macro implication is clear: India’s growth engine, which historically relied on a steady supply of household savings, now faces a thinner buffer.

India’s Debt Mix: The Global Outlier

Globally, household leverage is dominated by mortgages. Advanced economies like Australia (83.6% of GDP), Canada (72.9%), and the UK (57.4%) have deep mortgage markets. Even developing peers like Malaysia (54.7%) and China (38.7%) show significant home loan penetration. India, by contrast, sits near the bottom of the list at 11.2% of GDP.

Yet, the non-mortgage debt story is very different. India’s households carry 32% of GDP in non-mortgage liabilities, placing it among the highest globally—well above most advanced economies and comparable to South Korea (41.8%) and Thailand (57.2%). This debt is concentrated in personal loans, credit card outstandings, gold loans, and other short-duration borrowings rather than long-tenure, asset-backed mortgages.

Consumption is being financed more by debt and less by savings!

Why Job Creation and Salary Growth Are the Linchpins?

The key variable is income growth. If India can sustain high-quality job creation in manufacturing, services, and digital sectors, household incomes will rise, enabling both higher savings and more responsible borrowing. In that scenario, mortgage growth could accelerate into a multi-decade opportunity, while unsecured debt risks remain manageable.

But if job creation lags, households will continue to bridge the gap with high-cost debt. That erodes balance sheets, pressures lenders, and caps the potential of India’s consumption story.

The Bottom Line

The question is not just whether Indian households will save more or borrow less—it is whether they will earn more. Sustainable job creation and real wage growth are the foundation upon which both healthy savings and productive borrowing will rest.